A new study has been published in PNAS, titled “Why the US science and engineering workforce is aging rapidly“. The paper looks at data using the NSF’s Survey of Doctorate Recipients, and also uses U.S. Census data to get information about international researchers, to examine why the science and engineering workforce is aging. While there is a definite contribution from the general aging effect of the Baby Boomer population, aging is predicted to continue even without this effect.

The paper is discussed in Science, “As the U.S. scientific workforce ages, the younger generation faces the implications” and Inside Higher Ed, “50 Shades of Gray” and the authors are keen to point out that it is unknown as yet what the effects on the scientific enterprise of this aging may be, given that we can’t currently define well what differing contributions people at different ages make to science.

The paper supports previous work on the biomedical workforce by Misty Heggeness, who we interviewed previously on this subject of the aging biomedical workforce using NIH data, and with whom we also analyzed the biomedical workforce using Census data in “Preparing for the 21st Century Biomedical Research Job Market: Using Census Data to Inform Policy and Career Decision-Making” and “The new face of US science“.

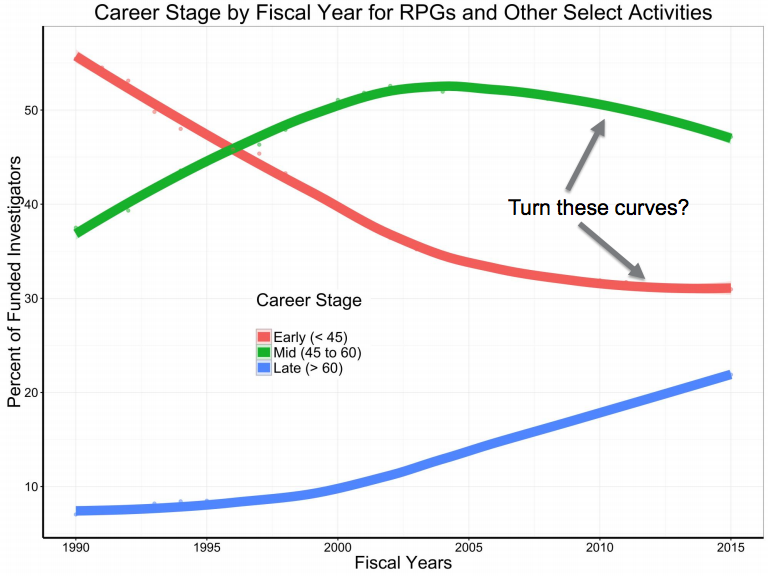

At the public session of the Next Generation Researchers Initiative in January 2017, Michael Lauer of the NIH pointed out that recent interventions have stabilized the percentage of funded investigators who are early career, but now mid-career investigators are starting to suffer as the percentage of funded investigators who are late stage continues to grow:

Also in this presentation, Michael Lauer showed:

- Funding success rates for all age brackets are less than half of what they were in 1980;

- The number of applicants continues to increase while the number of awardees remains static;

- The number of postdocs funded on research project grants and non-federal sources continues to increase;

- 10% of PIs get 40% of the funding.

Returning to Blau and Weinberg’s work, they discuss international researchers and find that the aging is essentially not affected by immigration; both U.S. citizen and non-citizen populations behave very similarly. one issue relates to international researchers and the lack of data about them. As we have shown, 52% of the biomedical workforce was foreign-born (18% naturalized citizens, 34% on visas, 48% U.S. citizens) and it is estimated that two-thirds of biomedical postdocs are not U.S. citizens. International researchers are referred to in the Science piece as “a group that is notoriously difficult to track“. However, despite repeated calls over decades to do so, information is not being collected, particularly about postdocs, that would make the tracking possible. This is why we and others have turned to the U.S. Census data, and other data sources, in an attempt to fill in the gaps.

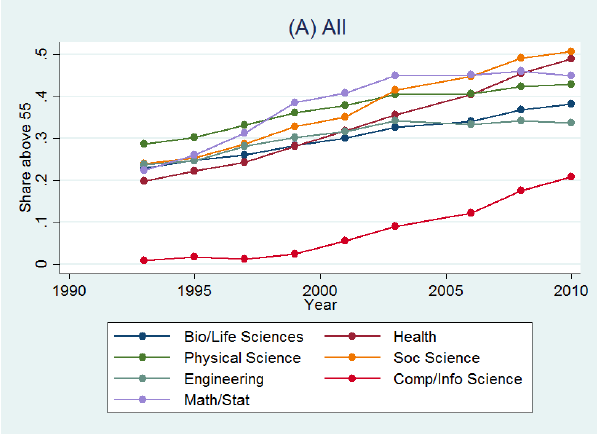

One interesting comparison with the biomedical data is in Supplementary Figure 5, the share of scientists in academia by age group:

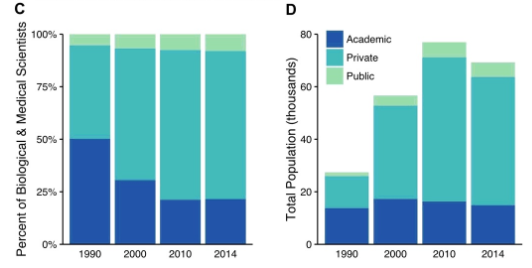

This data shows relatively little change over time, in contrast to our data on the biomedical workforce, which shows that the percentage of the workforce in academia halved in the same time, “C. & D. Industry composition (academic, dark blue; private, light blue; or public, light green) of biological and medical PhD scientists by year, as a percentage of the biomedical workforce (C) and total population (D)“. A break-out of this data by field therefore could be interesting:

You can find the paper and supplementary materials at PNAS here.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks